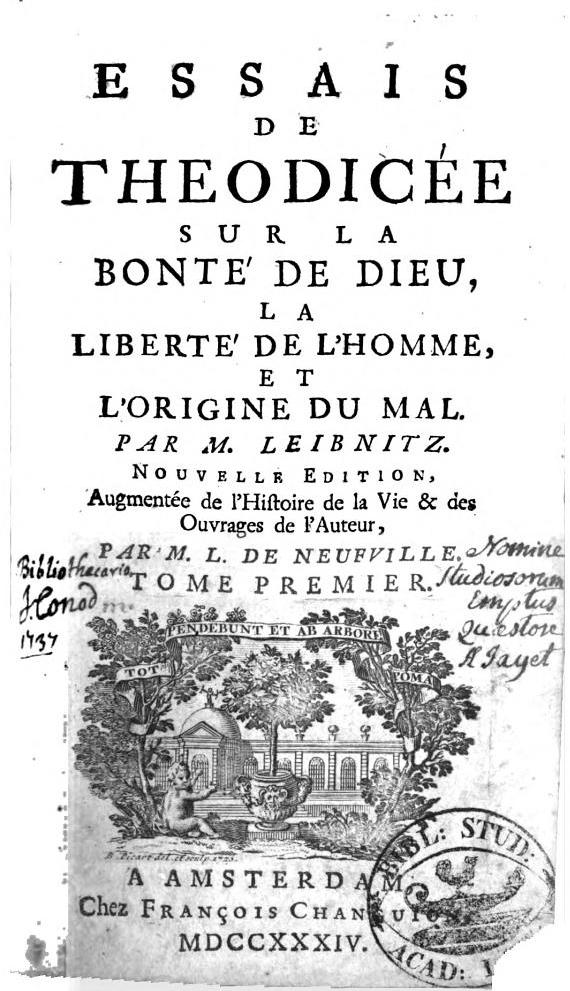

Leibniz, Theodicy

Theodicy is a philosophy classic by G. W. Leibniz. Leibniz was above all things a metaphysician. That does not mean that his head was in the clouds, or that the particular sciences lacked interest for him. Not at all–he felt a lively concern for theological debate, he was a mathematician of the first rank, he made original contributions to physics, he gave a realistic attention to moral psychology. Theodicy in its most common form, is an attempt to answer the question of why a good God permits the manifestation of evil. Some theodicies also address the evidential problem of evil by attempting “to make the existence of an all-knowing, all-powerful and all-good or omnibenevolent God consistent with the existence of evil or suffering in the world.” Unlike a defense, which tries to demonstrate that God’s existence is logically possible in the light of evil, a theodicy attempts to provide a framework wherein God’s existence is also plausible.The German mathematician and philosopher Gottfried Leibniz coined the term “theodicy” in 1710 in his work Théodicée, though various responses to the problem of evil had been previously proposed. The British philosopher John Hick traced the history of moral theodicy in his 1966 work, Evil and the God of Love, identifying three major traditions. The problem was also analyzed by pre-modern theologians and philosophers in the Islamic world. German philosopher Max Weber (1864–1920) saw theodicy as a social problem, based on the human need to explain puzzling aspects of the world.

Sociologist Peter L. Berger (1929–2017) argued that religion arose out of a need for social order, and an “implicit theodicy of all social order” developed to sustain it. Following the Holocaust, a number of Jewish theologians developed a new response to the problem of evil, sometimes called anti-theodicy, which maintains that God cannot be meaningfully justified. As an alternative to theodicy, a defense has been proposed by the American philosopher Alvin Plantinga, which is focused on showing the logical possibility of God’s existence. Plantinga’s version of the free-will defence argued that the coexistence of God and evil is not logically impossible, and that free will further explains the existence of evil without threatening the existence of God. Similar to a theodicy, a cosmodicy attempts to justify the fundamental goodness of the universe, and an anthropodicy attempts to justify the goodness of humanity. As defined by Alvin Plantinga, theodicy is the “answer to the question of why God permits evil”.

Theodicy is defined as a theological construct that attempts to vindicate God in response to the evidential problem of evil that mitigates against the existence of an omnipotent and omnibenevolent deity. As a response to the problem of evil, a theodicy is distinct from a defence. A defence attempts to demonstrate that the occurrence of evil does not contradict God’s existence, but it does not propose that rational beings are able to understand why God permits evil. A theodicy seeks to show that it is reasonable to believe in God despite evidence of evil in the world and offers a framework which can account for why evil exists. A theodicy is often based on a prior natural theology, which attempts to prove the existence of God, and seeks to demonstrate that God’s existence remains probable after the problem of evil is posed by giving a justification for God’s permitting evil to happen. Defenses propose solutions to the logical problem of evil, while theodicies attempt to answer the evidential (inductive) problem.

Download

Leibniz_Theodicy.pdf

Leibniz_Theodicy.txt

Leibniz_Theodicy.html

Leibniz_Theodicy.jpg

Leibniz_Theodicy.zip