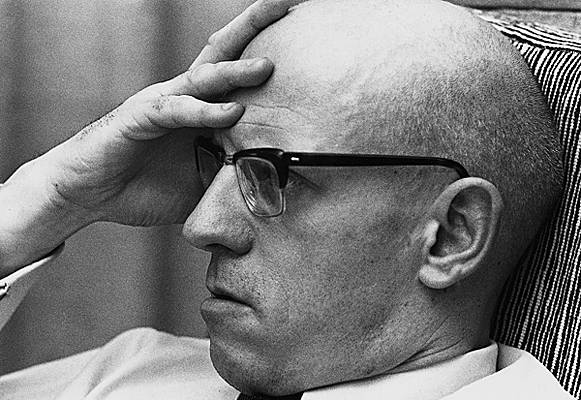

Foucault, The Order of Discourse

Discourse, as defined by Foucault, refers to:

ways of constituting knowledge, together with the social practices, forms of subjectivity and power relations which inhere in such knowledges and relations between them. Discourses are more than ways of thinking and producing meaning. They constitute the ‘nature’ of the body, unconscious and conscious mind and emotional life of the subjects they seek to govern (Weedon, 1987, p. 108).

… a form of power that circulates in the social field and can attach to strategies of domination as well as those of resistance ( Diamond and Quinby, 1988, p. 185).

Foucault’s work is imbued with an attention to history, not in the traditional sense of the word but in attending to what he has variously termed the ‘archaeology’ or ‘genealogy’ of knowledge production. That is, he looks at the continuities and discontinuities between ‘epistemes’ (taken by Foucault to mean the knowledge systems which primarily informed the thinking during certain periods of history: a different one being said to dominate each epistemological age), and the social context in which certain knowledges and practices emerged as permissable and desirable or changed. In his view knowledge is inextricably connected to power, such that they are often written as power/knowledge.

Foucault’s conceptual analysis of a major shift in (western) cultural practices, from ‘sovereign power’ to ‘disciplinary power’, in Discipline and Punish:The Birth of the Prison (1979), is a good example of his method of genealogy. He charts the transition from a top-down form of social control in the form of physical coercion meted out by the sovereign to a more diffuse and insidious form of social surveillance and process of ‘normalisation’. The latter, says Foucault, is encapsulated by Bentham’s Panopticon; a nineteenth century prison system in which prison cells were arranged around a central watchtower from which the supervisor could watch inmates, yet the inmates could never be certain when they were being watched, therefore, over time, they began to police their own behaviour. The Panopticon has became the metaphor for the processes whereby disciplinary ‘technologies’, together with the emergence of a normative social science, ‘police’ both the mind and body of the modern individual (see Dreyfus and Rabinow, 1982, p. 143-67).

Power, in Weedon’s (1987) interpretation of Foucault is:

a dynamic of control and lack of control between discourses and the subjects, constituted by discourses, who are their agents. Power is exercised within discourses in the ways in which they constitute and govern individual subjects (p. 113).

Foucault’s focus is upon questions of how some discourses have shaped and created meaning systems that have gained the status and currency of ‘truth’, and dominate how we define and organize both ourselves and our social world, whilst other alternative discourses are marginalised and subjugated, yet potentially ‘offer’ sites where hegemonic practices can be contested, challenged and ‘resisted’. He has looked specifically at the social construction of madness, punishment and sexuality. In Foucault’s view, there is no fixed and definitive structuring of either social (or personal) identity or practices, as there is in a socially determined view in which the subject is completely socialized. Rather, both the formation of identities and practices are related to, or are a function of, historically specific discourses. An understanding of how these and other discursive constructions are formed may open the way for change and contestation.

Foucault developed the concept of the ‘discursive field’ as part of his attempt to understand the relationship between language, social institutions, subjectivity and power. Discursive fields, such as the law or the family, contain a number of competing and contradictory discourses with varying degrees of power to give meaning to and organize social institutions and processes. They also ‘offer’ a range of modes of subjectivity (Weedon, 1987, p. 35). It follows then that,

if relations of power are dispersed and fragmented throughout the social field, so must resistance to power be (Diamond & Quinby, 1988, p. 185).

Foucault argues though, in The Order of Discourse, that the ‘will to truth’ is the major system of exclusion that forges discourse and which ‘tends to exert a sort of pressure and something like a power of constraint on other discourses’, and goes on further to ask the question ‘what is at stake in the will to truth, in the will to utter this ‘true’ discourse, if not desire and power?’ (1970, cited in Shapiro 1984, p. 113-4).

Thus, there are both discourses that constrain the production of knowledge, dissent and difference and some that enable ‘new’ knowledges and difference(s). The questions that arise within this framework, are to do with how some discourses maintain their authority, how some ‘voices’ get heard whilst others are silenced, who benefits and how – that is, questions addressing issues of power/ empowerment/ disempowerment.

Download

Foucault_The Order of Discourse.pdf

Foucault_The Order of Discourse.txt

Foucault_The Order of Discourse.html

Foucault_The Order of Discourse.jpg

Foucault_The Order of Discourse.zip