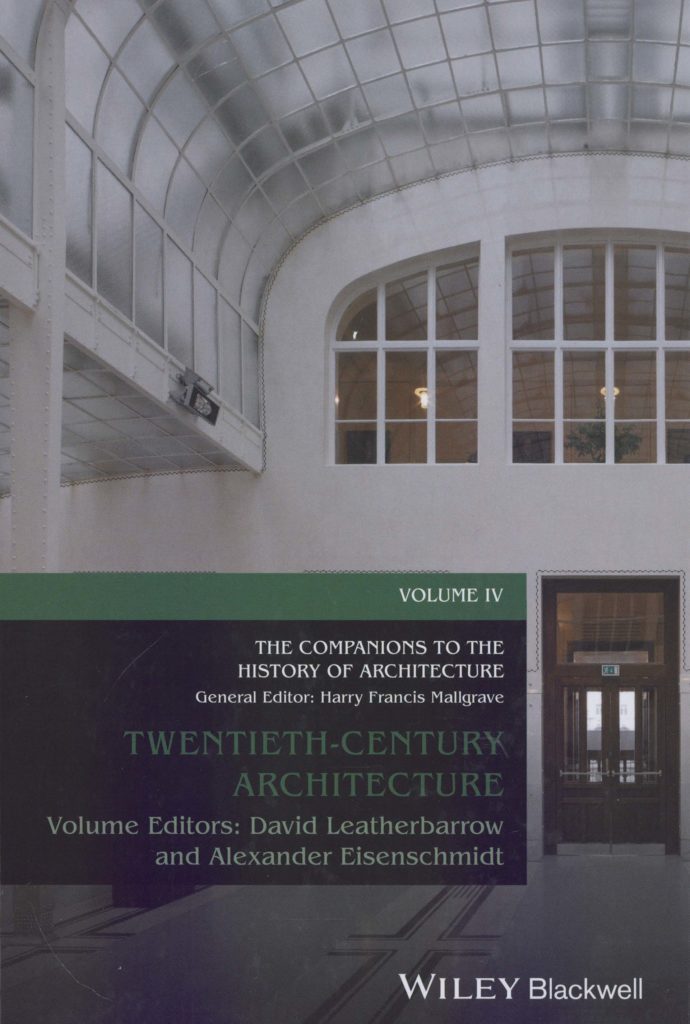

Leatherbarrow, Eisenschmidt, Twentieth Century Architecture

The progressive movements from the turn of the nineteenth century to the dawn of World War I largely preconditioned the modern avant-gardes that followed. All the buildings studied in the chapters of this section were designed by architects who were born at the end of the nineteenth century and practiced at the beginning of the twentieth century. They were part of a generation that witnessed unparalleled modernization first hand, an experience that deeply influenced the way they thought architecture had to engage the world. While the concept of the “modern” had been long in the making – from the seventeenth century quarrel against the supremacy of the ancients to the Enlightenment ideas of critical reason – industrialization brought about an unprecedented world, so radically transformed that its inhabitants struggled to recognize it. Modem life was catapulted into existence through urban developments that took place at a record pace, changing the world more rapidly and dramatically than ever before.

The industrial city witnessed an extreme urbanization, no longer composed of familiar expressions of communal intimacy, tom by political turmoil, and increasingly questioning established traditions and patterns of behavior. Modernization was intimately linked to the modem city, where the industrial environment with its factories, credit networks, new institutional systems, and communication and information technologies drew an unmatched number of workers to urban areas. The flow of migration into cities between 1800 and 1900 was dramatic and drastically changed urban-rural relationships. In Europe, London’s population increased from 1.2 to 4.5 million, and Berlin’s from 172,000 to 1.9 million. Cities in the United States surpassed these statistics, with New York growing from 60,000 to 3.5 million and Chicago developing from a settler’s village around 1800 to a metropolis with 1.7 million inhabitants. This rapid growth in population did not match the construction efforts, resulting in densities that in many cities reached its all-time high by the end of the nineteenth century. Observing an environment that sharply contrasted with the previously known world, Friedrich Engels wrote: “[the modem city is an] urban mess … and the result of a gigantic accident.” The poor working, living, and urban conditions of cities, were for Engels conditioned by modern industrial capitalism, giving The Companions to the History of Architecture, Volume IV, Twentieth-Century Architecture.

Download

Leatherbarrow_Eisenschmidt_Twentieth Century Architecture.pdf

Leatherbarrow_Eisenschmidt_Twentieth Century Architecture.txt

Leatherbarrow_Eisenschmidt_Twentieth Century Architecture.html

Leatherbarrow_Eisenschmidt_Twentieth Century Architecture.jpg

Leatherbarrow_Eisenschmidt_Twentieth Century Architecture.zip